Last night I gambled the blizzard on the Sydenham Bypass to make it to Holywood Methodist Church. Brian Rowan – a ‘veteran journalist’ if ever there was one – was in conversation with another well-known colleague, Mervyn Jess. The event was organised with the Centre for Cross Border Studies and was part of the Creative Holywood Festival.

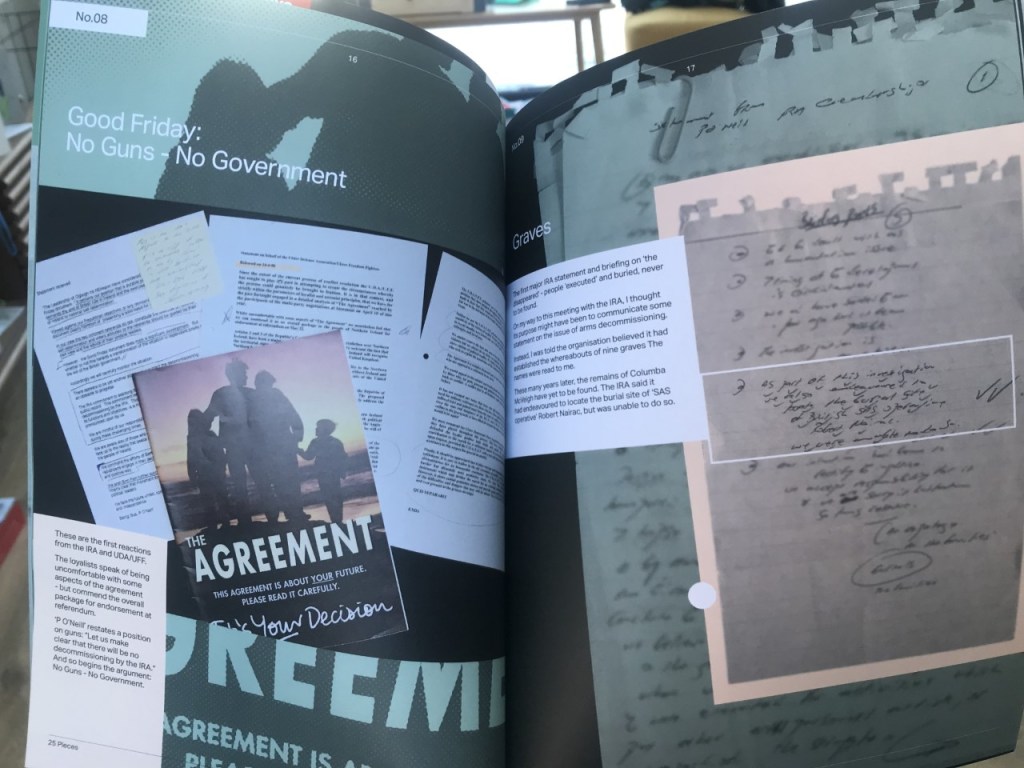

As a fan of significant and old bits of paper, the concept of the event appealed to me. It involved 25 documents from Rowan’s personal collection which charted the last thirty years of peace processing in Northern Ireland. It traced media history too: they ranged from paragraphs written on a typewriter, scribbles on a taxi voucher, to tweets.

It felt like half the peace process was in the church. Maybe, if there’d been no snow, the other half would have been there also. As Rowan discussed the documents, he called on various conflict/peace figures from all sides to add their thoughts on the moments he was discussing. It was a remarkable event format, as if people were walking out of history for cameos in a reconstruction, directed by a participant-chronicler of that history.

There were quite a few factual nuggets which were new to me, like the Ulster Unionists apparently knowing nothing about prisoner releases (one of the most difficult aspects of the Agreement for unionists) until the day before Good Friday. But always on the lookout for ‘the themes’, this is what I noted down:

- In the early 1990s, there were all kinds of un-coordinated conversations going on between church leaders, politicians, paramilitaries, and governments. Rowan called this ‘spaghetti junction’. In the cameo contributions, it was clear that no actor had the full picture at any one time. All a nightmare for historians, then.

- The peace process was not inevitable. The IRA ceasefire was not expected, and no one knew what it meant. The Agreement talks could easily have collapsed in the final days.

- There was also some interesting stuff about journalism in a peace process. Rowan recalled a time in 2000 when he felt compelled to report what he was being told – that the IRA was not going to decommission – even though he knew it would be bad for the peace process because it would spook unionists.

- There was, as is common, a certain amount of nostalgia for the political leadership of the 1990s. Progressive loyalist leader David Ervine, especially, appeared to have a great grasp of the role he had to play in 1998 in supporting Trimble. Rowan said that subsequently, amid the feuds of the early 2000s, ‘the peace process did not abandon loyalism, loyalism abandoned the peace process’.

Later in the event, we watched video interviews with young people about their hopes for Northern Ireland. I can reveal that those hopes did not involve violence, or more Orange-Green politics. They were probably in nappies for the DUP-Sinn Féin deal in 2007, never mind about 1998, and it occurred to me that if all you’d ever known were stop-start devolution and lots of conflict legacy controversies, without having experienced how we got here, you really would be befuddled. Or maybe not? What young people might really struggle to grasp is how extraordinary an event like this is – a conversation, a warm one even, between old foes. But we all get blasé about that kind of thing.

We had a closing word from Rev. Harold Good, another witness to much of this history. He jokingly denied it was a churchy ‘epilogue’, but that’s pretty much what it was, and it’s what was appropriate. With clerical gravitas, he noted the remarkable journeys of some of the people in the audience, and pointed out that there are still plenty of people in Northern Ireland who need to go on a journey. ‘Gratitude for the past, and trust in the future’, was his final message.

At the end, I ran in to a previous student of mine who, it turns out, is now working in an impressive field related to his course. Perhaps I should leave the house more often.

It was all being filmed, so if this event ends up on NVTV or somewhere, it’s worth a watch.

Leave a comment