In 1963, Ireland got its first escalator. The young Fintan O’Toole, ‘like every other kid in Dublin’, went to Roches Stores on Henry Street to try it out. There were actually two, and they ‘were magic carpets of modernity. Even the word was new and shiny: we had never imagined a need for such a verb, for such a motion, to escalate.’ His mind was blown.

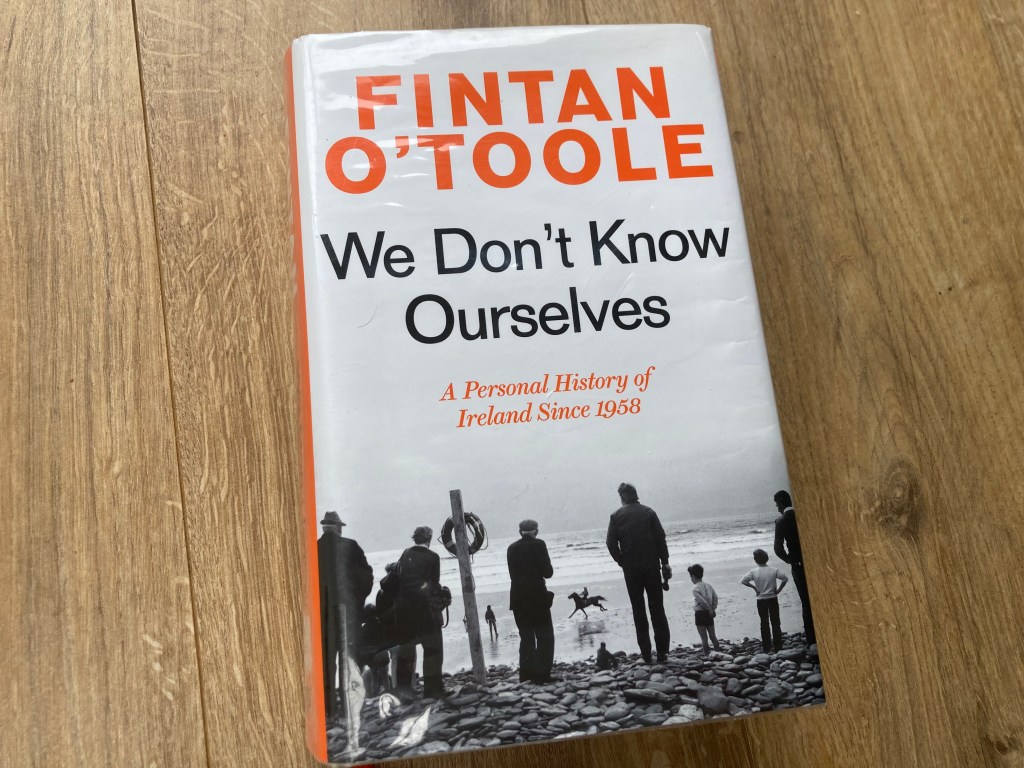

This passage in We Don’t Know Ourselves: A Personal History of Ireland Since 1958 (Head of Zeus, 2021) struck me because I’ve never forgotten my own moment of escalator-modernity shock. I was in Sligo one evening when I saw a gigantic item outside a building site, wrapped in thin white plastic that just about gave away what it was: Sligo’s first escalator, destined for Sligo’s first shopping centre, Quayside, then under construction. This was 2004.

Here was civilisation, on the back of a lorry. If Sligo, the town I’d lived in since 1988, was getting electronically moving stairs (of the type I rode on regular visits north of the border) something big really was afoot. The early 2000s was also the dizzying period when Sligo – technically a city – got its first public swimming pool, dual carriageways, and roundabouts, not to mention chain stores and immigrants.

Fintan O’Toole’s birth coincides with a pivotal moment in Irish history – TK Whitaker’s plan to modernise the economy. The book ends in 2018 with the referendum to legalise abortion. This story then is of the collapse of an old model of Ireland, or perhaps more accurately, the story of the surprising and dogged persistence of conservative and authoritarian forces long after they might have been expected to have weakened.

The marvelling at escalators indicates how people in Ireland have tended to be amazed and beguiled by modern things that seem to not quite properly belong there. Urbanism itself, O’Toole points out, has been alien in a land in which the national ideal has been rural. O’Toole grew up in Crumlin, a new suburb of Dublin: ‘Out here was pioneer territory, a kind of Ireland, suburban and working class, not known before. It seemed to many a blank space, physically and emotionally.’

Ireland in 1958 was backward by design. A good prequel to O’Toole’s book is Tom Garvin’s Preventing the Future: Why was Ireland so Poor for so Long? It shows how an alliance of vested interests (politicians, the church, famers, business, and Irish language promoters) deliberately resisted industrialisation, the expansion of education, social services, infrastructure and other elements of the modern state that much of Europe was busy acquiring. We Don’t Know Ourselves is a chronicle of how Ireland – and in particular, three movements that claimed to embody true Irishness, the Roman Catholic Church, the Fianna Fáil party, and militant republicanism – were dragged into the modern world.

Who did the dragging? Globalisation, feminist and LGBTQ+ activists, the eventual exposure of the crimes of these organisations, and the lived reality of ordinary people which never matched the pious and suffocating ideal put abroad by elites.

But perhaps people in conservative, underdeveloped Ireland were happy enough? The emigration figures dispel that notion. The Irish revolutionaries had fought for an independent state that, it turned out, people could not live in. Over forty percent of those born in Ireland between 1931 and 1941 left. Some people thought that the Irish might die out. A terrific chapter dissects the multiple meanings of JFK’s visit to Ireland in 1963, one of which was that it painfully rubbed in his good fortune that his Wexford ancestors had had the sense of escaping this miserable island.

From 1958, Ireland is in search of a viable way to be Irish. It couldn’t mean to be British, so perhaps it meant to be American, or European? If rural life was unbearable, could being Irish involve living in suburbs and embracing consumption, clocking-in in factories run by Germans or Americans? The hope of the political elite was that modernity could come without disturbing the conservative Catholic social order. In a chapter on the origins of RTÉ, O’Toole shows that it was eventually set up in 1962, not out of any enthusiasm for media, but due to concerns that so many people in Ireland were able to receive broadcasts from across the border and the Irish Sea. Better, the authorities thought, that Irish people be provided with content in keeping with Irish morality which was of course of a much higher standard than pagan/Protestant Britain.

An Irish-style conservative modernity appeared possible before the revelations of Church and state wrongdoing in the 1990s. Until then, the contradictions were sustained by the one thing Irish people excelled at: doublethink. O’Toole maintains this intriguing theme throughout the book. The country was pervaded by a ‘culture of unknowing’: a capacity for cognitive dissonance, seeing yet not seeing, harbouring massive open secrets.

The Church enforced strict standards of morality yet sinned demonically. Everyone knew about that predatory local priest, about the abuse in Church institutions, and yet at the same time, nobody did. People were dutiful Catholics yet experts in moral workarounds. Financial authorities saw massive corruption but took no action. The country kidded itself that it was classless because class division was a British thing. Irish republicans blew innocent people to pieces in the name of freedom and equality. None of this could last.

Of life and politics in Northern Ireland, we don’t see much, but there are brilliant chapters on ‘the Troubles’ and peace process, notably, a sobering review of 1972. Such was the depth of disorder that year that O’Toole remembers his father telling him and his brother, gravely at the dinner table, that the three of them would probably be sent to fight in the north.

This book will be a personal journey for any Irish reader – perhaps a hard or impossible one, depending on your closeness to the darker realities covered. I was a northern blow-in to the Republic, but the book explained much about the earlier processes and decisions that led to the (bleak) condition of the west of Ireland in the 1990s. There’s even a chapter on how country and western music took over the west. Once I reached the 1990s chapters, the names of so many dodgy politicians, clerics, and businessmen came back to me, half-remembered from news coverage of scandals and tribunals.

It’s redundant to say that this book is well written. O’Toole is one of Ireland’s most celebrated writers. Even so, for such a long book, there is remarkably little filler; the skilled storytelling and profound analysis are addictive. The ‘personal history’ bits – when O’Toole shows himself as a kind of extra in historical events, or his experience as revealing of the times – are always well-judged.

However, We Don’t Know Ourselves is (and I am not sure if this is a criticism or not) almost entirely negative. Might the gloom have been lifted occasionally by talking about, say, the success of Irish sports stars, musicians, or films? Do the Irish have any virtues? There are some heroes, but villains dominate, the biggest being the omnipotent Archbishop McQuaid and corrupt politician Charlie Haughey. We are not quite sure what to make of Gay Byrne, the broadcaster.

And a charitable observer might argue Ireland looks slightly better when set alongside other places. For all its failings, it was at least a peaceful democracy in a period in which there were dictatorships in southern and eastern Europe, colonial wars being fought by Western European powers, and racial segregation in the US.

But O’Toole is not interested in excuses. He is interested in skewering hypocrisy and clearing away myths. External standards are irrelevant because Ireland did not live up to its own standards. Now, the future is unknown – as it always is – but, O’Toole concludes, ‘What is possible now, and what was entirely impossible when I was born, is this: to accept the unknown without being so terrified of it that you have to take refuge in fabrications of absolute conviction’.

Leave a comment