Back in the mid-nineties, a local character known to our family had a standard joke when he met any of us. ‘Ha look it’s the Mitchell Commission!’ We didn’t see the humour because we knew lots of Mitchells, cousins and the like. But Mitchell was not a common name in Sligo, and ‘Mitchell’ was a staple in the news at the time because ex-US Senator George Mitchell was at the centre of the Northern Ireland peace process.

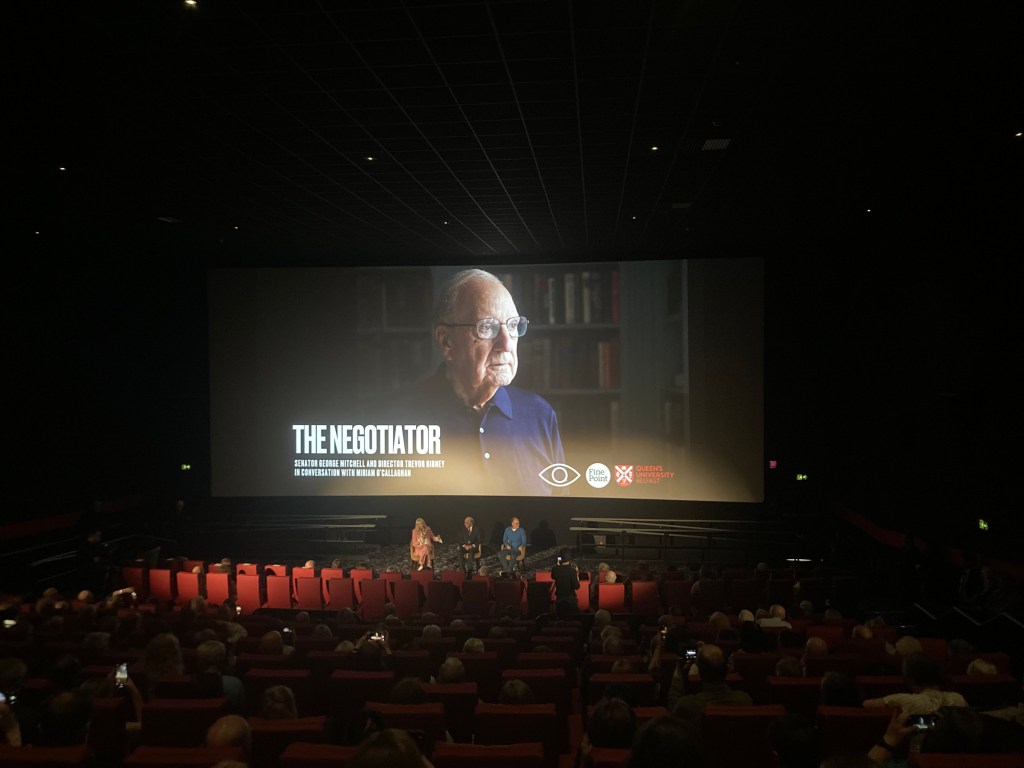

He is the subject of this new documentary which premiered at the cinema in the Odyssey complex in Belfast, as part of the Docs Ireland documentary film festival. Commissioned by Queen’s University Belfast, The Negotiator is neither a complete biography of Mitchell nor a fulsome account of the peace process. Instead, it tries to explain the making of the man who was to have such an historic professional success on 10 April 1998. We follow his involvement in Northern Ireland from 1995 on, nominated by Bill Clinton as trade envoy, then becoming chair of the Mitchell Commission on weapons decommissioning, then chair of the multi-party talks.

This narrative is intercut with key episodes in his earlier life told through an enjoyable abundance of archive footage and photos, plus the talking heads of old associates. This biographical material, as the director Trevor Birney pointed out in his introduction to the film, is not well known in Northern Ireland.

I certainly wasn’t aware that Mitchell’s origins were genuinely humble. His grandparents were Irish immigrants, and his father married a woman from a Lebanese immigrant family who lived close by. In the documentary, Mitchell wells up as he recalls his father’s dedication to bringing him regularly to the library, despite not being educated himself. A schoolteacher also took him under her wing, giving him increasingly challenging reading material. He only attended university thanks to the support of a family friend. Oh, and he was a US intelligence officer in 1950s Berlin!

One of the most significant moments in the film comes near the beginning, when it covers a period which brought him to national attention in the US: the senate hearings into the Iran-Contra scandal in 1986. The military man at the centre of the affair, Oliver North, claims he was doing it all for God and country. But Mitchell, a former judge, is shown calmly telling him that in fact, it is quite possible to love God and country but to come to very different conclusions to Oliver North.

This is the first intrusion of one of the unmentioned ghosts that haunt the film, Donald Trump, he who is guiding the ground rules of democracy through the shredder. Much of the film feels like an episode of The West Wing, a nostalgic visit to a universe in which the US is run by intelligent and honourable public servants. Paying tribute to Mitchell’s ability to work with Republicans, Nancy Pelosi says wistfully that ‘it was a different time to now.’ She thought Mitchell should have run for President.

My main interest was in how the film covered the making of the peace process and the Good Friday Agreement. Here it falters. Mitchell is presented as the benevolent American who came to pacify the warring tribes of ‘Protestants and Catholics’ – that, in fact, is how we see that the US media appears to have reported it at the time.

We do not learn about the complicated long-term forces that led to the Agreement (military stalemate, new republican strategy, backchannel talks, peace activism, geopolitical change), nor do we learn much about the details of the talks process. John Hume and moderate nationalism is almost entirely absent from the film, as are the Women’s Coalition and Alliance Party. Instead, we have the mandatory but dispiriting appearances of Bill Clinton, Tony Blair, and Gerry Adams, individuals who might be better placed in a documentary about how to start wars rather than end them.

This brings us to the other unseen ghost in the film: the list of extremely hot wars currently raging. Mitchell’s main peace lesson appears to be patient and respectful listening. Yet current wars look more like games played by military-industrial complexes and ideological fundamentalists, rather than mutual disagreements that might be amenable to dialogue and better understanding.

Still, human agency always matters. And George Mitchell was certainly the right person in the right job at the right time. When the wars of today do come to an end, wise people will need to be involved. Ireland benefitted from Mitchell’s immense talents, and to those, the film is a fitting tribute, even if it doesn’t quite succeed as history.

Many people of my age will have thought George Mitchell old in 1998. That means he’s really old now: ninety-one. But he’s a good leading man on screen. His lucid and charming tones, and his gentle ‘Bawston’ accent, resonated around the cinema. One can easily imagine how he did ease difficult conversations, both in Belfast and Washington DC. His wife, too, whom I had never encountered before, appears several times and is a terrific presence.

The film was followed by a Q&A with Birney and Senator Mitchell, hosted by Miriam O’Callaghan of RTÉ. Mitchell stressed that the Good Friday Agreement was never meant to be perfect or permanent, giving politicians license to reform it. He did emphasise the importance of civil society and the Women’s Coalition specifically. The real heroes, he said, are the people of Northern Ireland who pushed their politicians to end the conflict. There were two standing ovations.

*

After the event, we came out of the cinema into a balmy evening, close to the glassy buildings and spacious walkways that line the river. Hanging around were journalists and political party people, veterans of 1998 as well as younger notables, sharing jolly greetings. I’d bumped into a former student, Heather, who told me she had worked on the film. I had come with friends and neighbours, Tim and Julie, and their teenage daughter Evie. In a nice reversal of what one would expect, it was Evie who had known about the event and was the reason her parents and I were all there. She’d learned about Mitchell in History class.

Maybe it was the Mitchell effect, the bright mid-summer night, or the half-bottle of free beer I’d drunk, but I felt a glow of pleasure and appreciation at all these realities and connections – what might cumulatively be described as peace.

Leave a comment