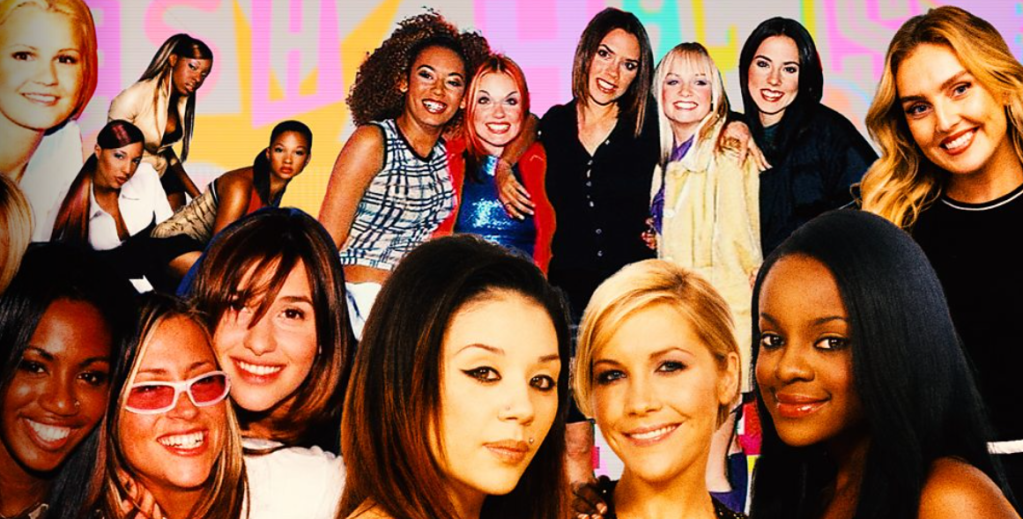

Girlbands Forever, a three-part documentary charting the history of girl groups in the UK since the 1990s, has just aired on the BBC. When I finished it, I watched Boybands Forever which came out in 2023.

There’s a market for this kind of 1990s/2000s nostalgia and I’m it. Yet is it nostalgia when the past is revealed to have been so much more sinister than one could have imagined?

Pregnant members of All Saints were told they should have abortions. Eternal were taken away to the countryside so the record company could control what they ate. Scott from Five appears to have had a mental breakdown, asked to leave or have a break from the band, and was told, sorry mate. Lee from 911 says they were so overworked they ‘couldn’t even control their piss’.

So the dream of fame which became real for the few, but was dangled before the many, was empty, and now we can get our own back by watching TV documentaries about the backstage misery of our idols. Perhaps that’s spiteful of us, but it’s not quite that simple because the fate of these people is so varied. Compare Robbie Williams, still a star and interviewed in the exclusive resort of Gstaad in Switzerland, to John from East 17, who looks to be in his local pub, says he made no money from fame, and went straight back to roofing.

But much of the entertainment here is not schadenfreude but the ongoing psycho-drama between the all-powerful managers and the bands they put together. These teenagers became both kids the managers had to care for and products they had to market. There is no love lost between Robbie Williams and Take That manager Nigel Martin-Smith, nor between Brian McFadden of Westlife and their puppet-master Louis Walsh. (It was surreal to see footage of Sligo in the mid-90s including a performance of IOU, the Sligo boyband (!) which I remember, and which was the precursor – before Walsh and Simon Cowell fired three of them and added two Dubliners – to Westlife.)

The managers are complex characters, as we’d expect people involved in such an unusual enterprise to be. The dollar signs are visibly sewn into their eyeballs. Simon Cowell (inevitably) is on hand to deliver the cold truth: that in return for fabulous success, popstars agree to give up their time and their ability to live a normal life.

But there is real affection and appreciation between some of the bands and their bosses. It seems significant that most of the managers were themselves very young – in their early to mid-twenties. Members of Five and Atomic Kitten say that there really should have been more adults around to look after them back in the day, a sad comment. Most of these performers were working-class, catapulted, often in a few months, from school or work as security guards and checkout assistants into wealth and the merciless glare of the tabloids. It was highly odd, as many of them reflect.

We learn about some big ‘what ifs’. McFadden appears to regret leaving Westlife when he did. When Five realised they couldn’t go on and broke up, they were about to break America. Mis-teeq, too, a talented, unmanufactured group from the UK garage scene, were on the cusp of global fame when their record company went bust. They weren’t picked up again, but one member of the trio, Aleesha Dixon, was.

Then there are the fascinating afterlives. Take That reformed as a ‘man band’ and became bigger than ever. But Tony Mortimer says he regrets East 17’s reunion and none of that group even speak to each other now. The band 911, whose USP appears to have been that they were short, are still huge in south-east Asia.

I would have been curious to hear more about the music itself – how the bands’ sounds and styles were developed; we do learn that Five turned down Britney’s ‘Baby One More Time’. And what happened to the fans, the (mostly) girls who pressed their faces into fences and stomachs over crash barriers, tearfully declaring their eternal love? We walk among these people daily! The manager of East 17 is shown saying at the time of the group’s fame that he wasn’t selling music, he was selling sex – a correct articulation of what pop music has always been about. We don’t learn much in these documentaries about the emotional legacy of years of being touted as sexual objects, or how the stars reflect on their collusion with this.

There is perhaps an equally intriguing documentary to be made about the making of these documentaries. The absences are telling, or at least we can’t help assuming they are. No Spice Girls are in it, allowing Eternal and All Saints (both of which predate the Spice Girls) free reign to slag them off. Only one member of Take That, Robbie Williams, is featured, someone who comes across as a person who likes to have his say. (Williams is a ‘good storyteller’ says Nigel Martin-Smith, not a compliment). There is not even a mention of One Direction or Girls Aloud, sadly two bands which have members who have died. We worry about the absence of East 17’s Brian Harvey, a central figure whose declining mental health is much discussed.

This kind of contemporary cultural history shows how much has changed in relatively little time. Or at least, it raises the question of how much has changed. For instance, bands like Damage, Eternal (after Louise Redknapp left) and Mis-teeq confronted the prejudice that all-black bands didn’t sell magazines. The mental health of stars wasn’t considered. Homosexuality was covered up. Much has changed – but what revelations about today’s entertainment industry will be made in a documentary in twenty years’ time?

In the end, we are left wondering about the series titles: ‘forever’ – meant ironically, surely, given how so much of the subject matter covered is either forever in the past, or should be forever in the past. Girlbands Forever ends on a positive note about how girls will always need these empowering role models. Robbie Williams is happy in his sagely middle age.

But the overriding impression left by the six hours of interviews and old footage is that this was an era of collective madness and cruelty which belongs in the dustbin of history, and the documentaries themselves are part of the shared journey back to sanity. Some great tunes, though.

Leave a comment