In the summer of 2024 we went to Cornwall for the first time. It was a blank slate and I wrote a blog post of fairly shallow first impressions. ‘Cornwall: Ireland but better?’ was my explosively provocative title. What I meant was, ‘Ireland but with more people and things to do’. In a straight up beauty contest, Ireland wins.

But Cornwall got under my skin in that way that we want places to get under our skin, and happily we returned this July past, swapping our grim Premier Inn for a stone holiday cottage in Mousehole (pronounced Mow-zul), a serene fishing village a few miles west of the already far west Penzance. I’ve also been reading about Cornwall – to check the validity of some of those first impressions, and to extend my stay.

Mousehole

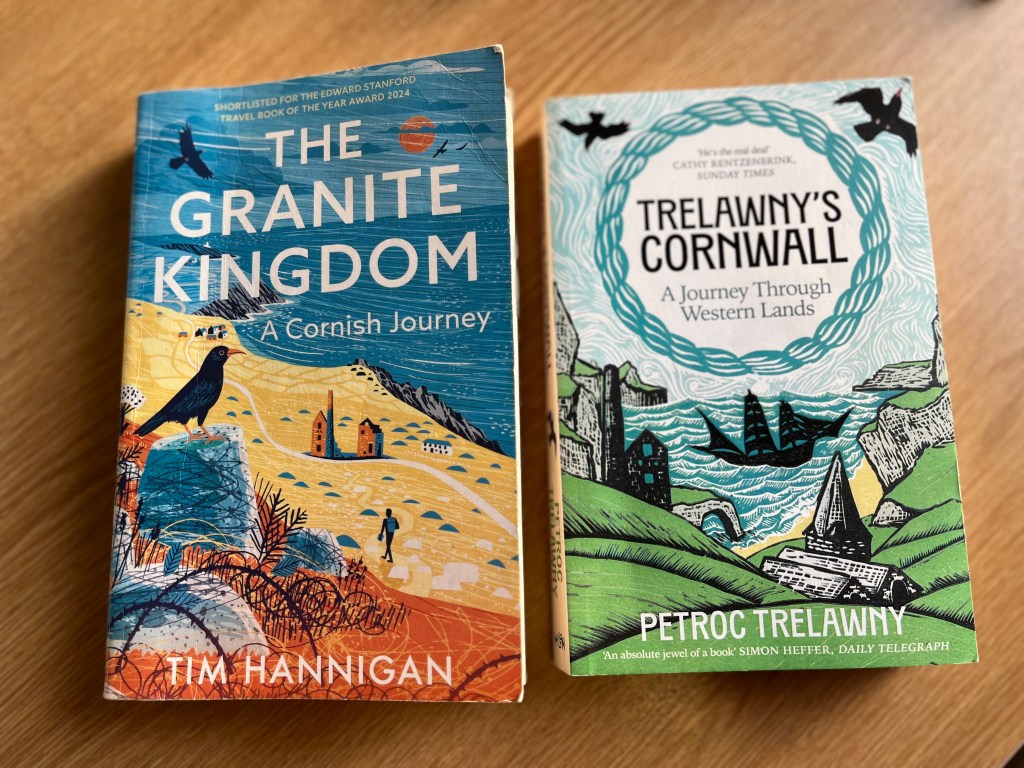

The comparison with Ireland gets some endorsement from Tim Hannigan, a travel writer and scholar from Cornwall but living in Ireland. He begins The Granite Kingdom by observing that ‘Cornwall is closer to Cork or Brest than it is to London’. The landscape has ‘a clear topographical kinship with coastal Brittany or the west of Ireland: the same ragged foreshore; the same bedrock bursting through the thin skin of the land’. His book is a travelogue of walking the region, combined with a forensic investigation into what makes Cornwall distinctively Cornish.

The book shows how everyone from racist anthropologists, ‘Celtomaniacs’, tourism promoters, and tellers of smuggling and piracy tales have romanticised and exoticized Cornwall, mainly for an English audience. It’s been a sun-drenched idyll and an inhospitable wasteland populated by primitives. But the realities of the Cornish experience have been more prosaic: fishing and mining hardship, emigration, and Methodist routine.

I’d been struck first time by all the Methodist churches, and it turns out that religion is part of Cornwall’s distinct character. Petroc Trelawny is a BBC Radio 3 presenter from Cornwall, and like The Granite Kingdom, Trelawny’s Cornwall is a tour based on theme and location, but with more memoir and very fine-grained local history.

Trelawny recalls that at school he was marked out by not being Methodist. In the eighteenth century, founder of Methodism John Wesley preached vigorously and frequently all over the county. Cornwall had been neglected by the Anglican Church while the Wesleyan message spread quickly through the growing mining communities.

But ecclesiastical dissent can be traced back further: both Trelawny’s and Hannigan’s books describe the Prayer Book Rebellion, when the Cornish protested the Tudor Crown’s imposition of the English-language Book of Common Prayer in 1549. The quashing of the protests left an imprint of anti-state grievance. Methodism was all about personal spiritual experience and the involvement of non-clergy in church life, and so the movement would provide an egalitarian alternative to the hierarchical English church.

Methodist observance plumitted in the late twentieth century; Trelawny visits a Methodist chapel now used by the Muslim community. But you wonder about the legacy of all this. That laidback and unpretentious atmosphere that I’d picked up on last year can only exist in places of relative equality. Hannigan, interestingly, remembers his local area in Penwith as ‘an eclectic and strangely classless place’. This he attributes not to church denomination but ‘the steady trickle of drifters-down’, that is, the long-standing attraction of Cornwall for artists and alternative types.

Our base of Mousehole was a mile along the coast from Newlyn, the UK’s biggest fishing port. A minibus takes people along this bit of coast. Every day I watched it, becoming more and more jealous of its occupants, until early one morning I took it, concocting a pointless trip to Newlyn to buy a coffee. I like looking at harbours although there is not much to Newlyn itself. But this little place once gave birth to style of art, the ‘Newlyn School’.

Newlyn

Hannigan explains how the artists who began to appear in the 1880s didn’t actually want to capture Cornwall and the Cornish as they were at the time, but an older world of simple fisher folk untouched by modernity. Another ‘artist colony’ emerged in St. Ives a few decades later and later still, in Lamorna, a dot on the map to which we walked from Mousehole via the stunning coast path.

Depictions of Cornwall as rural and backward belie the truth that Cornwall was as industrialised, and is now as deindustrialised as, say, the north of England. We learn a lot in both books about the colossal mining industry and the related story of the Cornish diaspora. Skilled Cornish miners were in demand all over the world, especially as demand waned at home. Cornwall is still a relatively poor part of the UK. Today’s economic story is the seasonal overtourism and the demand for holiday accommodation which prices out locals. (Sorry.)

Both Trelawney and Hannigan devote chapters to tourism in Cornwall. It followed the railways in the nineteenth century and then, as now, poverty wasn’t necessarily visible to holidaymakers. With tourism came the ‘tourist gaze’ and the construction of Cornwall as the exotic-at-home – English, yet also somehow both Celtic and Continental. Trelawney begins his book by taking the sleeper train from London to Penzance, a service called ‘The Night Riviera’.

This year I noticed another thing that might be part of Cornwall’s hard-to-pin-down appeal: the fact that it’s basically an island – a peninsula almost sliced off by the Tamar river, the ancient border. As a visitor, you have two coasts to play with (boat trips, everywhere!) But it takes commitment to get to Cornwall in the first place and then to navigate those crazy roads.

Falmouth

Yet this was once one of the best-connected locations in the world, the communications hub of the British Empire. The Post Office ran its ‘packet service’ out of Falmouth’s vast and deep harbour from the late 1600s to the early 1800s, sending ships to ports all over the Americas and western Europe. This was because William III, Ulster’s favourite Dutchman, entered war with France, making the English Channel dangerous to shipping. You can learn about all this in the National Maritime Museum in Falmouth which, when we were there, also had an enjoyable exhibition on the history of surfing in Cornwall.

Meanwhile, Trelawney tells about how Porthcurno, a coastal village, if even that, in the far west, became the landing site for Britain’s undersea communications cables (something that has been in the news recently due to Russian interest in such things). This made it a location of existential significance during the World Wars. Then, further along the coast at Poldhu, the Italian engineer Marconi built transmitters which sent the first transatlantic wireless communication in 1901.

Porthcurno is a headache to get to but we were determined to return this summer because last year, I had stalled on making a decision (as I like to do) and we missed the chance to go to a show at the Minack Theatre, a remarkable venue carved out of the cliff side, opened in 1932. This time we booked for a comedy play but left at the interval due to the absence of laughs and the intensity of sunshine. We headed down to the stupidly pretty beach and an invading phalanx of tiny jelly fish, eventually leaving Porthcurno in another collective huff. What we should have done was visit the Museum of Global Communications, just on the other side of the beach car park.

Minack Theatre, Porthcurno

Cornwall doesn’t have blockbuster attractions – no defining landmarks or even dominant resorts. It’s about the totality. When we were there, now and again I’d exclaim, ‘Isn’t it good to just be in Cornwall!’ These books are low key but rich and deep studies of place. And as ever, the more specific you get, the more universal you get, and you end up thinking about the unfathomable depth of human experience in all places. Hannigan and Trelawny take you to Cornwall which, in the absence of the time, money or patience to make the real journey, is all we want.

Leave a comment